While many recognize the 1990s as a time of the labor movement’s resurgence in Los Angeles, for garment workers, it was a time of existential crisis. Facing new competition from imported goods, local manufacturers returned to old ways of doing business, hiring mainly undocumented immigrants, firing union activists, and severing long-standing contracts. A raid on an apartment complex in El Monte revealed how dangerous the exploitation had become: the CA Department of Industrial Relations found 72 Thai women, victims of human trafficking, being held against their will and forced to sew for 18 hours a day. The clothing investigators found in the apartment was sold at major national retailers, including Robinson’s May, Montgomery Ward and Mervyn’s.

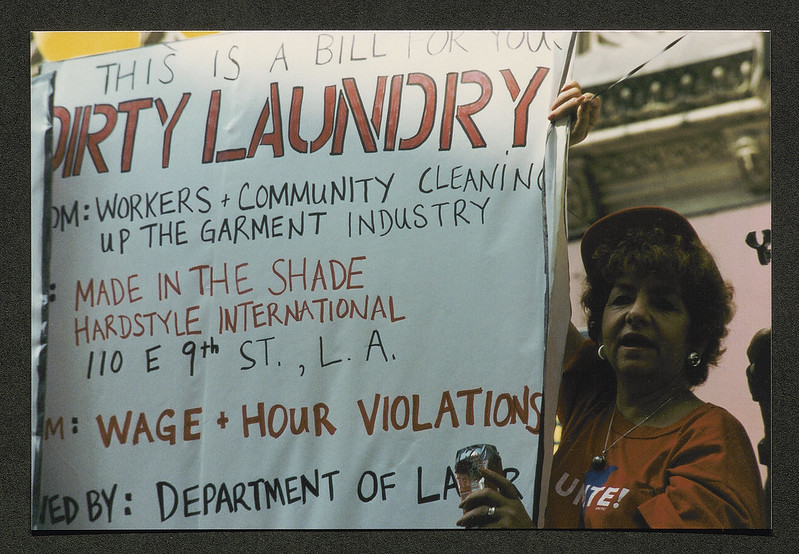

The incident in El Monte—which occurred amidst UNITE’s years-long campaign against Guess? Jeans Inc., Los Angeles’ largest apparel manufacturer—prompted UNITE! and its allies to rethink their tactics. It made clear to garment workers that they needed legislation to establish Joint Liability, so that manufacturers like Guess? And retailers like Robinson’s May could be held accountable for conditions to which they subcontracted their work. Previous attempts to pass similar legislation had been vetoed by governors Wilson and Deukmejian, but after Assemblywoman Hilda Solis introduced the new bill, AB633, Gov. Gray Davis expressed his support. AB633 increased registration fees to fund additional inspectors, established an expedited process for wage theft claims and introduced successor employment liability so that subcontractors couldn’t simply close their shops to avoid paying fines. Unfortunately, almost immediately, major retailers in Los Angeles challenged the law in court, claiming the new rules did not apply to them, and the fight for Joint Liability continued.

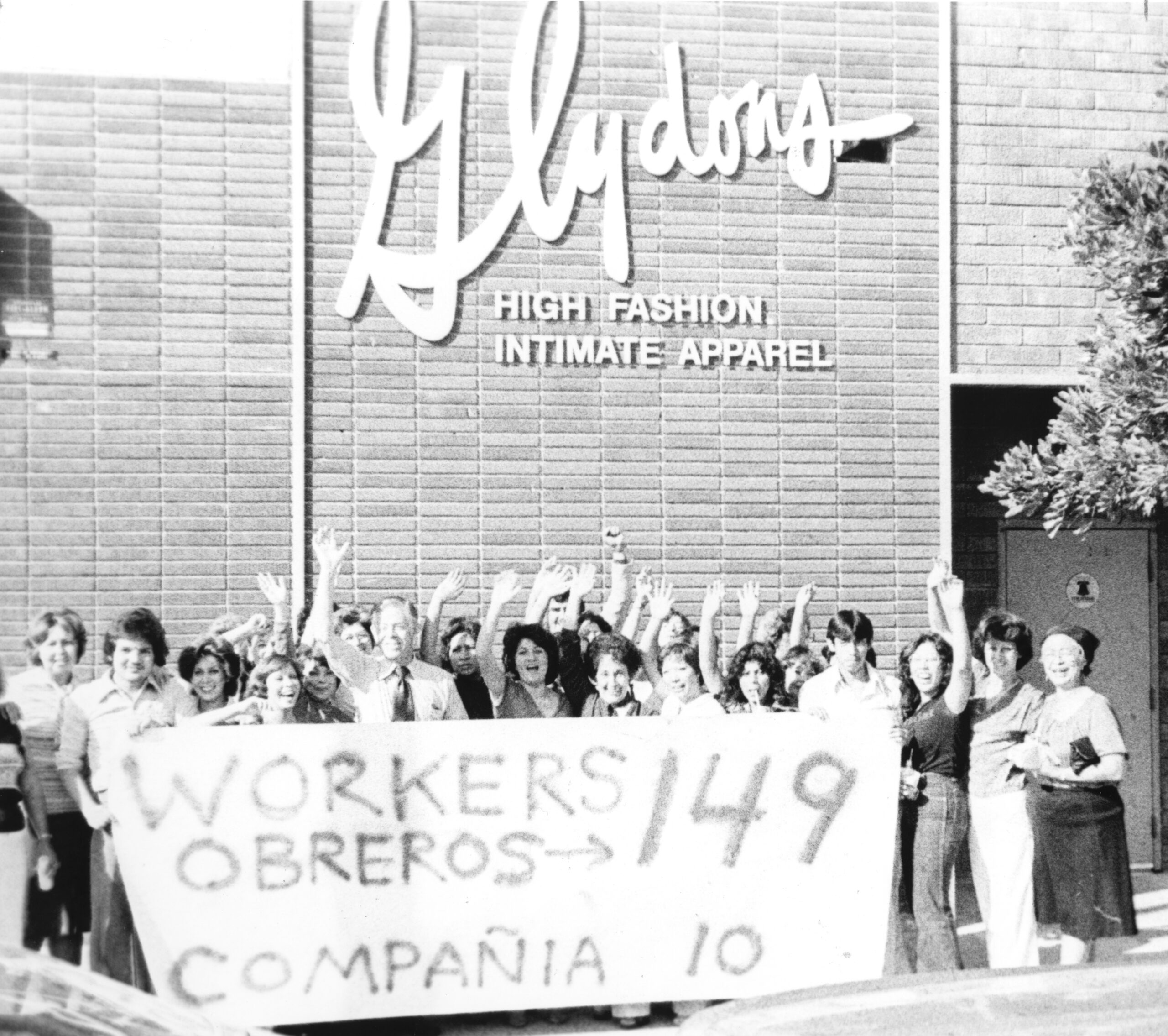

Pictured here: Assemblymember Hilda Solis and Father Pedro Villaroya of CLUE stand with Thai workers from El Monte at UNITE! rally, while organizer Cristina Vásquez speaks at a retailer-accountability demonstration at the Robinsons-May store in Santa Monica, CA in December 1997. From the Steve Nutter Collection, IRLE Archives.

For more about AB633, read: Blasi, Gary, and University of California Institute for Labor & Employment. 2001. Implementation of A.B. 633 : A Preliminary Assessment / Gary Blasi and Associates. Los Angeles: Institute for Labor and Employment, University of California, Los Angeles.