The members of SEIU-USWW gathered at the union hall in May 2011 to share their stories, memories, photographs, clippings, and artifacts. Long-time union member Victoria Marquez brought an extensive collection of documents, buttons, t-shirts, and other items. Later, she shared her life story with Andrew Gomez as part of a UCLA Oral History Research Center project. You can listen and read along here.

Tag: Justice for Janitors

Justice for Janitors (JfJ) is a campaign of the Service Employees International Union (SEIU). JfJ in Los Angeles was part of SEIU local 399, local 1877, and currently United Service Workers West (USWW).

-

That stopped everything

Rosa Beltran reflects on the power of rank-and-file union members

La huelga del 2000 fue una victoria— Yo estaba fuera de mi edificio piqueteando 24 horas seguidas, 24 horas deteniendo, durmiendo, pegado a los containers de basura porque como Uniones, si la Unión de los basureros miraba un janitor que estaba piqueteando, se respetaba eso. El UPS [United Parcel Service] si miraba a alguien piqueteando, respetaba eso. El correo, si miraba a alguien, no había movimiento de nada. Ahí se detenía todo; pero si no había nadie, es por eso que le digo yo de qué sirve tener un sindicato con ejecutivos con buenas ideas, si soldados no habemos. Porque los soldados somos los que llevamos a cabo todo, al final del día. Ésa es la representación que nosotros tenemos.

The strike of 2000 was a victory— I was outside my building picketing 24 hours in a row, resting and even sleeping by the dumpsters because the unions, if the sanitation workers saw a janitor who was picketing, they respected that. If UPS saw someone picketing, they respected that. The postal workers, if they saw someone, nothing moved. That stopped everything; but if there had been no one there, that is why I say what good is it having leaders with good ideas, if you don’t have soldiers. Because at the end of the day the soldiers are the ones that carry it all. That is the representation we have.

From the interview of Rosa Beltran by Andrew Gomez.

16175256 {:WCFSSIZK} 1 chicago-fullnote-bibliography 50 default 462 https://socialjusticehistory.irle.ucla.edu/wp-content/plugins/zotpress/ -

Una Causa Justa | A Just Cause

This editorial from La Opinion reflects the widespread support for the Justice for Janitors campaign in the Spanish-speaking community of Los Angeles. The writer argues that the janitors' demands are modest, and that their aggressive campaign reflects a broad dissatisfaction with the power structure in LA. Translated from Spanish by Stephanie Dyer.

A Just Cause, La Opinion, April 6, 2000

Janitors, those informal workers who are responsible for the cleaning of the nation’s skyscrapers and buildings, carry out a tough job that is generally nocturnal and poorly compensated. The majority of them are immigrants, some undocumented, with families that depend – often entirely – on their meager income. They perform a humble job that is little known but important. Every morning, when millions of office workers and professionals report to their jobs to start their workday, the janitors have already fulfilled their duty. The offices, the hallways, and the restrooms are ready so that the world of production continues to function flawlessly.

This week, the Los Angeles janitors, who are among the lowest paid in the country but have also woven an effective organization over the years to defend their interests, made the decision to resort to a strike to demand fairer wages. This is an extreme measure, certainly, but so is their situation. Even representatives of the companies they work for recognize that these workers’ wages are outdated in comparison to wage realities in Los Angeles.

As known, this is one of the most expensive areas to live in America. But it is, at the same time, one of the most privileged, especially in these times of rampant prosperity. Corporate profits have climbed to dizzying heights, but the janitors and other workers have to fight with wages that are barely above the minimum, with which one can hardly survive. There is enough wealth in California for those who clean offices to have a decent, basic wage that permits them a dignified life and resources to educate their children. This has been recognized by the county Board of Supervisors and by several local officials who have declared their sympathy for the strikers, whose latest crusade has radiated from downtown Los Angeles to cities such as Burbank, Glendale, Beverly Hills, El Segundo and Woodland Hills.

The janitors’ claim is not limited only to the interests of their labor union. In reality, the red and black banners that call for justice and have begun to rise proudly as of Monday, speak equally for other sectors that also work hard and that, like the janitors, still await the success that is boasted about so much to arrive where they are.

Translation by Stephanie Dyar

Original text: http://proquest.umi.com/pqdweb?did=493361091&Fmt=3&clientId=1564&RQT=309&VName=PQD

-

We call each other sister unions

Rocio Sáenz recalls the spirit of solidarity among unions in the early 1990s

I come from Mexico City, and I had a union there. Even though, looking back at the unions in Mexico, they were often very corrupt, at the time I thought it was better than nothing. When I came to the U.S., I did a lot of different jobs. I was a domestic worker, I was a salesperson in a store, and stuff like that. But I wanted to be in a unionized workplace, and so I was trying to get a job through a local union. I didn’t know that there was such a thing as being an organizer, but I was making posters and banners for he ILGWU. A few months later, I met someone in Local 11 of HERE and they hired me. Even then, for a few months, I didn’t do organizing. I didn’t even know what it was. But then I got very involved.

I saw a different way to organize [in HERE]. To bring the trust back from the members, and to show that this was a different union. In any organizing drive, you have to show the workers that, yes, you can make a difference. Little victories that you have to deliver, in order to say there is a change. It has to be very, very specific and concrete. And you have to see things as industry-wide. When I was with HERE I remember organizing my first hotel, reorganizing it for the first time in then years. That was in Manhattan Beach, close to the airport. We did it through elections. Well we organized 300 workers, and that was not going to make a big difference for the industry. You have to look at the whole industry, instead of one single work site. You have to do it in a market competitive way. If you’re going to organize, it has to be like all of downtown L.A. has got to go union. It has to be a long-term plan It takes a lot of effort, a lot of persistence, and a lot of resources.

(more…) -

Justice for Janitors 1995 Strike News

English and Spanish TV news coverage of street actions leading up to the 1995 strike by SEIU Local 1877, the Justice for Janitors campaign. Featured speakers include Mike Garcia, Rocio Saenz, and Jono Shaffer. Differences in style and presentation between English and Spanish-language reports suggest parallel public views of unions, inequality, and immigration.

The original video tape and others are available to researchers at the UCLA Library Department of Special Collections:

16175256 {:R3IGW5US} 1 chicago-fullnote-bibliography 50 default 967 https://socialjusticehistory.irle.ucla.edu/wp-content/plugins/zotpress/. -

Building sustainable peace in Guatemala, the union perspective

From the 1970s to the 1990s, the Central American nations of El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Guatemala experienced civil war, government-sponsored death squads, and genocide. Many who fled the violence settled in Los Angeles were they joined other immigrant workers in low-wage service sector jobs, and became part of the unionization drives of the 1990s. Immigrants workers then mobilized their unions in support of the peace process by welcoming visiting delegations and lobbying federal officials. This flyer documents the visit of Guatemalan union leader Rodolfo Robles to SEIU Local 399 in the early 1990s. His union, representing Coca Cola workers, played a leading role in the opposition to military dictatorship by urban workers. Learn more about Justice for Janitors.

-

Cleaning Workers to Go on Strike: October 19, 1990

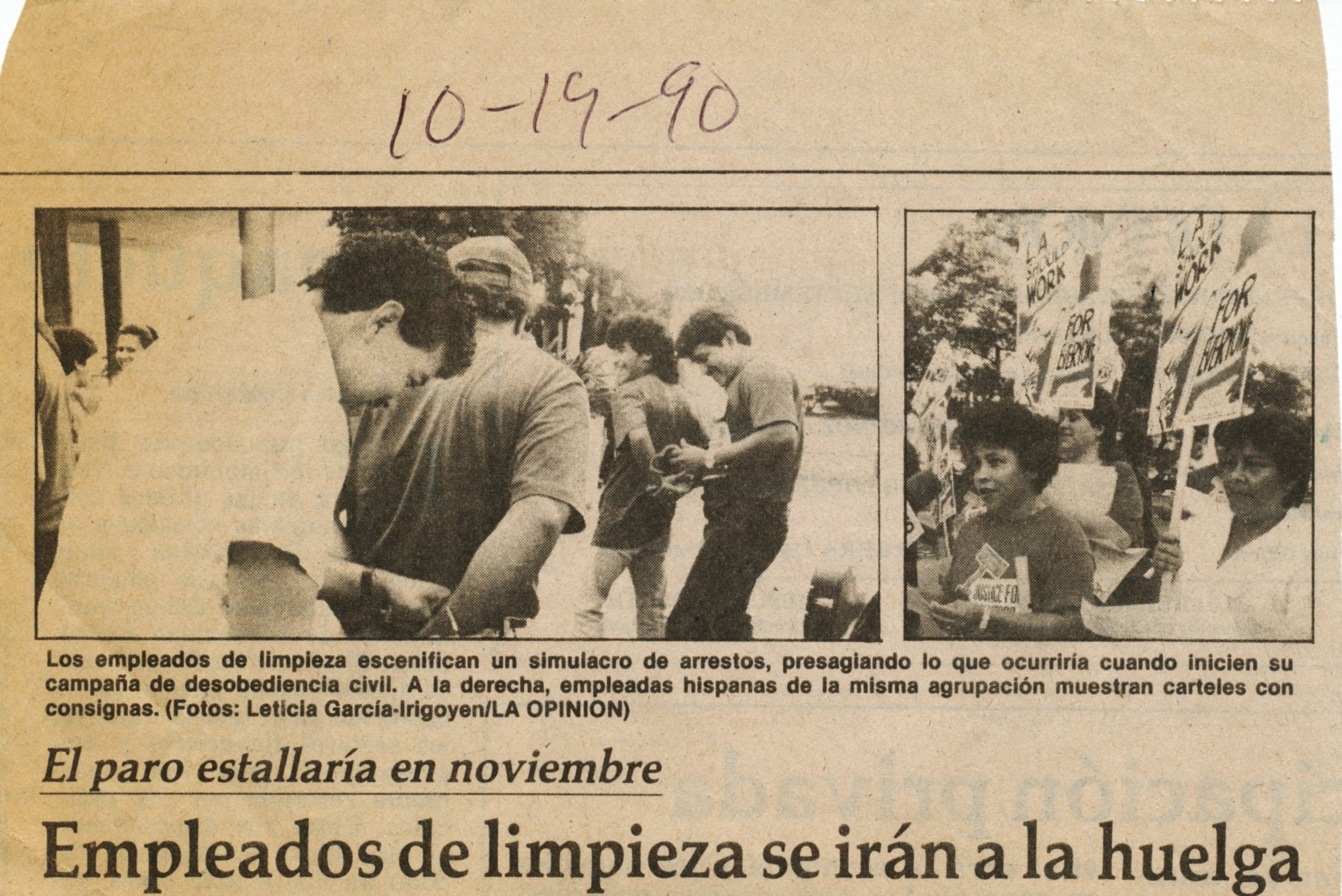

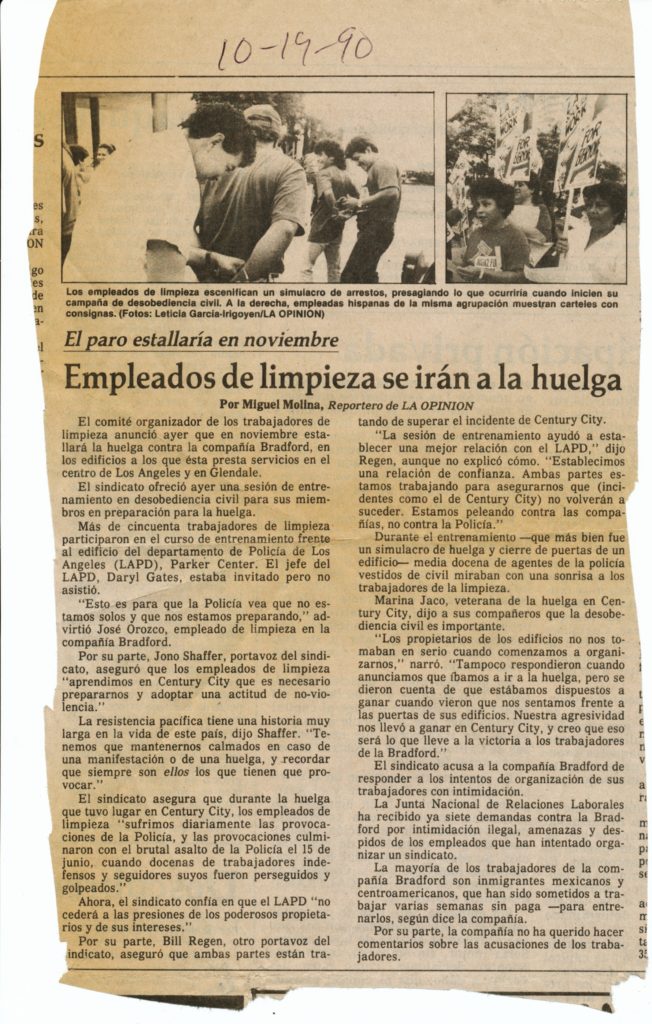

A clipping of a 1990 article describing a Justice for Janitors training held in from of the Los Angeles Police Department. Janitors were preparing to use non-violent civil disobedience in their strike on Bradford Building Services in November of that year. Translated from Spanish by Juan Torres.

“Cleaning workers to go on strike” La Opinion, October 19, 1990

By Miguel Molina

Image caption: Janitors stage an arrest drill to prepare for what will occur as a result of their civil disobedience campaign. To the right, Hispanic women janitors from the same group show signs with slogans. (Picture by Leticia García-Irigoyen/ La Opinion)

Yesterday the committee that organizes cleaning workers announced that on November a strike against the Bradford Company in the buildings in which they provide their service located in the center of Los Angeles and in Glendale.

La Opinion reports on janitors’ preparation for a 1990 strike The union offered courses of civil disobedience to its members in preparation for the strike.

More than 50 cleaning workers participated in this course in front Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) building, located in Parker Center. LAPD Chief, Daryl Gates, was invited to the training but he did not attend.

“This it to show the police that we are not alone and that we are preparing,” warned Jose Orozco, janitor in the campaign against Bradford.

Jono Shaffer, spokesman for the union, assured that the janitors “in Century City learned that it is necessary to prepare ourselves and adopt an attitude of non-violence.”

Peaceful resistance has a long history in this country, said Shaffer. “We have to keep calm in a demonstration or strike and always remember that they are the ones who have to provoke.”

The union assures that during the strike in Century City “we suffered daily provocations by the police that culminated in the police assault on June 15, when dozens of janitors and supporters were chased and beaten.”

The union believes that now LAPD “will not consent to the pressures of the powerful proprietors and their interest.”

Another spokesman for the union, Bill Regen, assures that both parties are trying to overcome the Century City incident.“The training course helped established a better relationship with LAPD,” said Regen, although he did not explained how. “We established a relationship of trust. Both parties are working to assure that (incidents like the one that occurred in Century City) will not occur again. We are fighting against the corporations, not against the police.”

During the civil disobedience training–which realistically was more of a strike and shut down of the building’s doors training– half a dozen plain clothes police looked on with a smile at the janitors.

Marina Jaco, a Century City strike veteran, said to her janitor partners that civil disobedience is important.

“The owners of the building did not take us seriously when we started to organize,” Jaco said. “They also did not respond when we announced we were going on strike, but they realize that we were willing to win when they saw us sitting outside the doors of their building. Our aggressiveness allows us to succeed on the Century City strike, and I think this will carry to victory in the campaign against Bradford.”

The union accuses Bradford Company for intimidating any efforts to organize workers into a union.

The National Labor Relations Board has received seven complains against Bradford’s illegal intimidation practices, threats, and lay off of workers who have attempted to organize a union.

Most of the workers from Bradford Company are immigrants from Mexico and Central American, who have been compelled to work without pay for weeks, supposedly to train them.

Bradford did not comment on the workers the accusations.

-

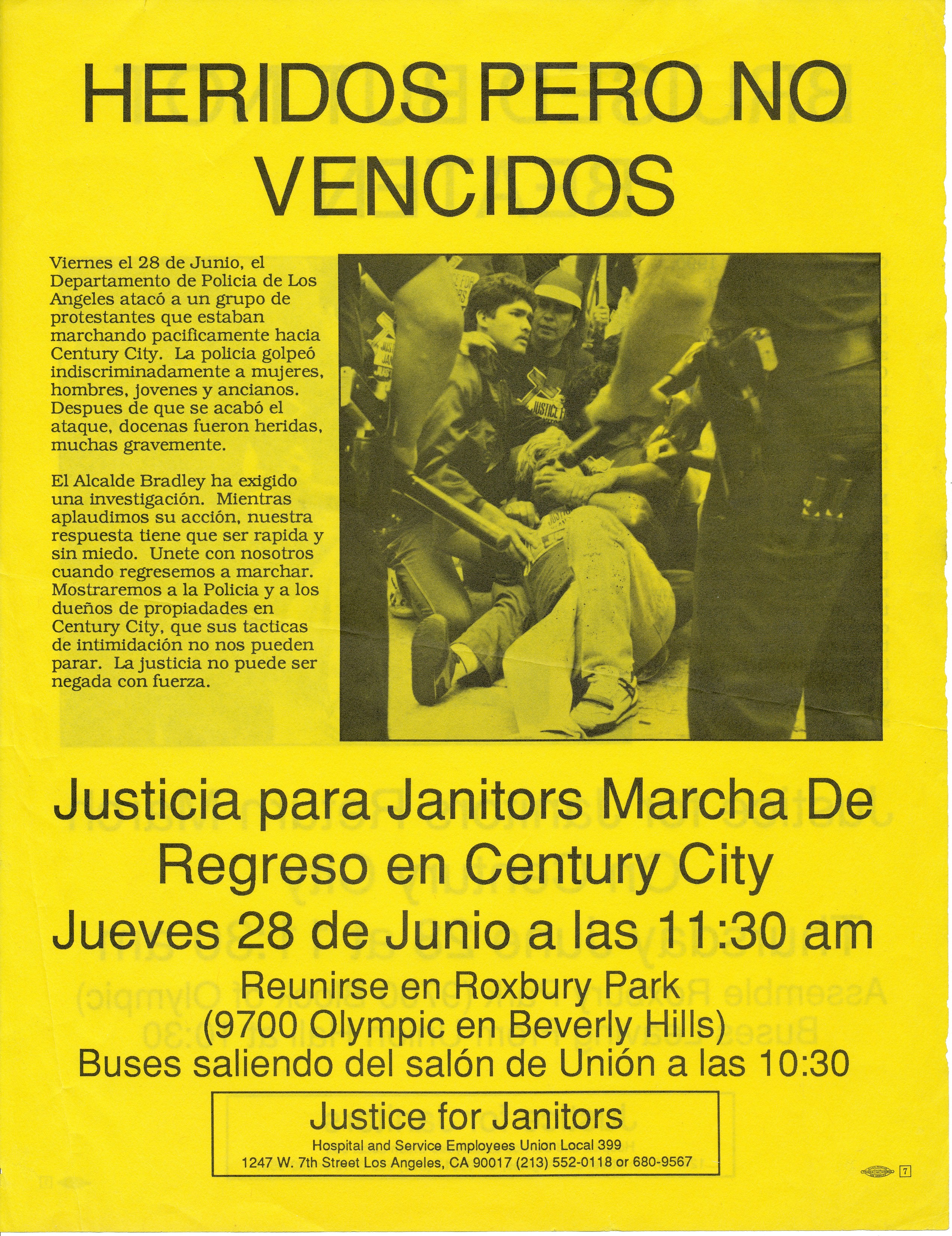

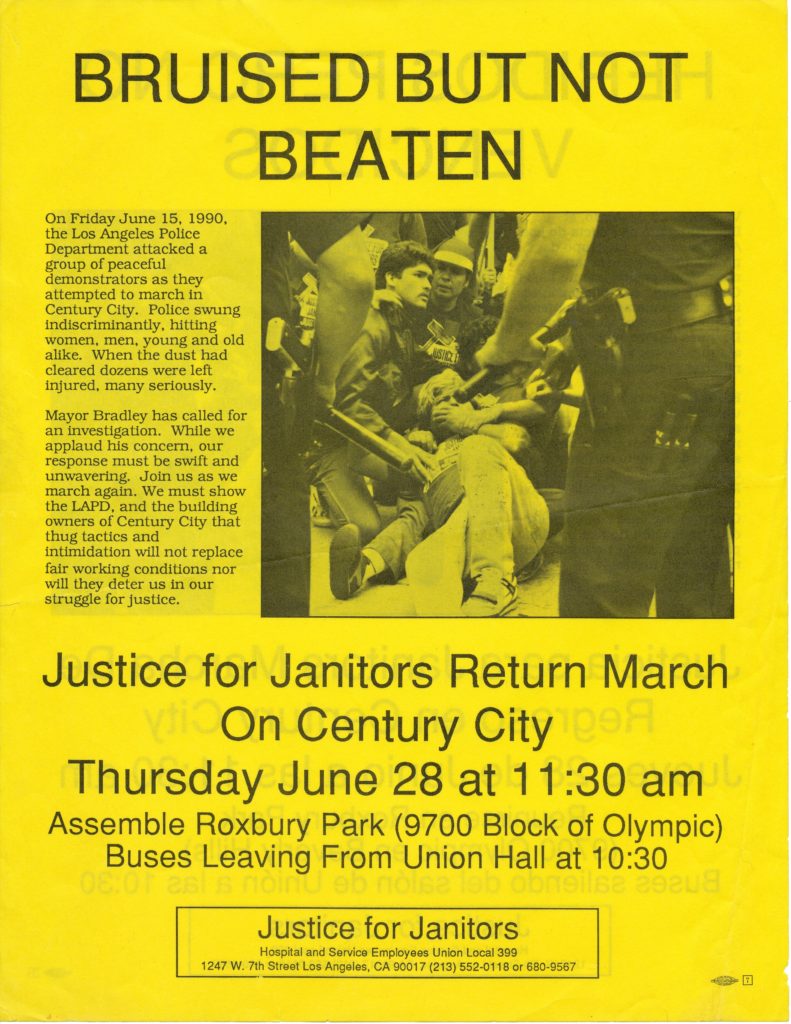

Bruised But Not Beaten | Herridos pero no vencidos

Justice for Janitors pamphlet announcing a return march to Century City. On June 15, 1990, the LAPD armed with nightsticks attacked group of peaceful demonstrators outside Century City that included women and children. Not intimidated by police brutality, the demonstrators continued to protest until fair working conditions were given.

-

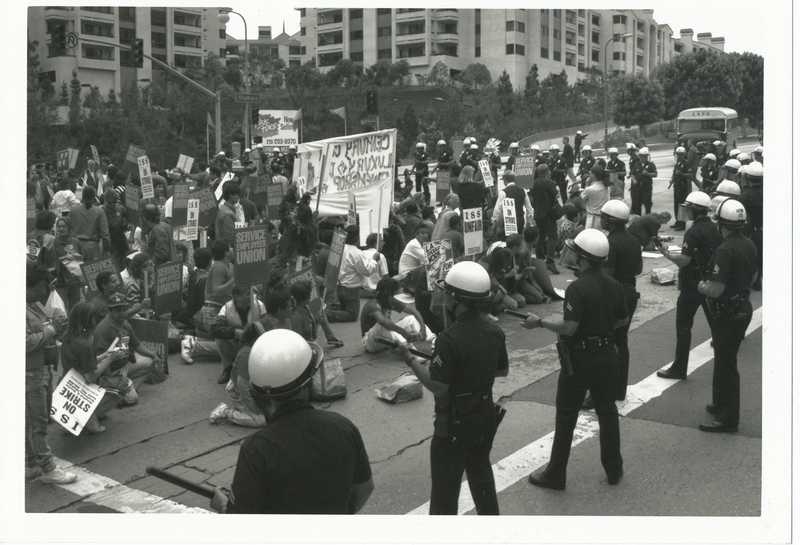

Police disrupt janitors march on Century City, June 1990

During a 1990 strike against cleaning contractors in the Century City office complex, Los Angeles police confront and beat janitors and their supporters. The confrontation led to a city inquiry into police officers’ actions, and a settlement between janitors and their employers. This video compilation was produced by the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) and shared with other locals on VCR tapes before being converted to digital and distributed via YouTube.

16175256 {41191:MBRQ4UEX} 1 chicago-fullnote-bibliography 50 default 970 https://socialjusticehistory.irle.ucla.edu/wp-content/plugins/zotpress/%7B%22status%22%3A%22success%22%2C%22updateneeded%22%3Afalse%2C%22instance%22%3Afalse%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22request_last%22%3A0%2C%22request_next%22%3A0%2C%22used_cache%22%3Atrue%7D%2C%22data%22%3A%5B%7B%22key%22%3A%22MBRQ4UEX%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A41191%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Baker%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221990-06-16%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%201.35%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%26gt%3BBaker%2C%20Bob.%20%26%23x201C%3BPolice%20Use%20Force%20to%20Block%20Strike%20March%20Labor%3A%20About%20Two%20Dozen%20Demonstrators%20Are%20Injured%20during%20Protest%20by%20Janitors%20in%20Century%20City.%3A%26%23xA0%3B%5BHome%20Edition%5D.%26%23x201D%3B%20%26lt%3Bi%26gt%3BLos%20Angeles%20Times%20%28Pre-1997%20Fulltext%29%26lt%3B%5C%2Fi%26gt%3B%2C%20June%2016%2C%201990%2C%20sec.%20Metro%3B%20PART-B%3B%20Metro%20Desk.%20%26lt%3Ba%20class%3D%26%23039%3Bzp-ItemURL%26%23039%3B%20href%3D%26%23039%3Bhttp%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fsearch.proquest.com%5C%2Flatimes%5C%2Fdocview%5C%2F281089965%5C%2FCBC4CFD8B6684D0BPQ%5C%2F14%3Faccountid%3D14512%26%23039%3B%26gt%3Bhttp%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fsearch.proquest.com%5C%2Flatimes%5C%2Fdocview%5C%2F281089965%5C%2FCBC4CFD8B6684D0BPQ%5C%2F14%3Faccountid%3D14512%26lt%3B%5C%2Fa%26gt%3B.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22newspaperArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Police%20Use%20Force%20to%20Block%20Strike%20March%20Labor%3A%20About%20two%20dozen%20demonstrators%20are%20injured%20during%20protest%20by%20janitors%20in%20Century%20City.%3A%5Cu00a0%5BHome%20Edition%5D%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Bob%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Baker%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22Most%20of%20the%20injured%20demonstrators%20suffered%20cuts%20or%20bruises%20during%20the%20half-hour%2C%20shriek-punctuated%20confrontation%2C%20which%20took%20place%20around%201%20p.m.%20as%20the%20demonstrators%20were%20marching%20toward%20a%20planned%20rally%20at%20several%20Century%20City%20office%20towers%20where%20janitors%20went%20on%20strike%20May%2030.%5CnPolice%20made%20no%20immediate%20attempt%20to%20arrest%20the%20demonstrators.%20Instead%2C%20after%20a%20standoff%20of%20several%20minutes%2C%20police%20briefly%20attempted%20to%20prod%20the%20demonstrators%20to%20disperse%20by%20shoving%20and%20then%20hitting%20them%20with%20batons.%5CnAfter%20that%20initial%20conflict%2C%20the%20demonstrators%20backed%20up%20a%20few%20feet.%20Several%20minutes%20later%2C%20they%20stood%2C%20many%20of%20them%20linking%20arms%2C%20and%20walked%20toward%20the%20police%20line.%20There%20was%20contact%20between%20the%20two%20sides%20and%20police%20began%20to%20force%20demonstrators%20back.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22Jun%2016%2C%201990%22%2C%22section%22%3A%22Metro%3B%20PART-B%3B%20Metro%20Desk%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22English%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%2204583035%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fsearch.proquest.com%5C%2Flatimes%5C%2Fdocview%5C%2F281089965%5C%2FCBC4CFD8B6684D0BPQ%5C%2F14%3Faccountid%3D14512%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222015-12-31T00%3A32%3A29Z%22%7D%7D%5D%7DBaker, Bob. “Police Use Force to Block Strike March Labor: About Two Dozen Demonstrators Are Injured during Protest by Janitors in Century City.: [Home Edition].” Los Angeles Times (Pre-1997 Fulltext), June 16, 1990, sec. Metro; PART-B; Metro Desk. http://search.proquest.com/latimes/docview/281089965/CBC4CFD8B6684D0BPQ/14?accountid=14512. -

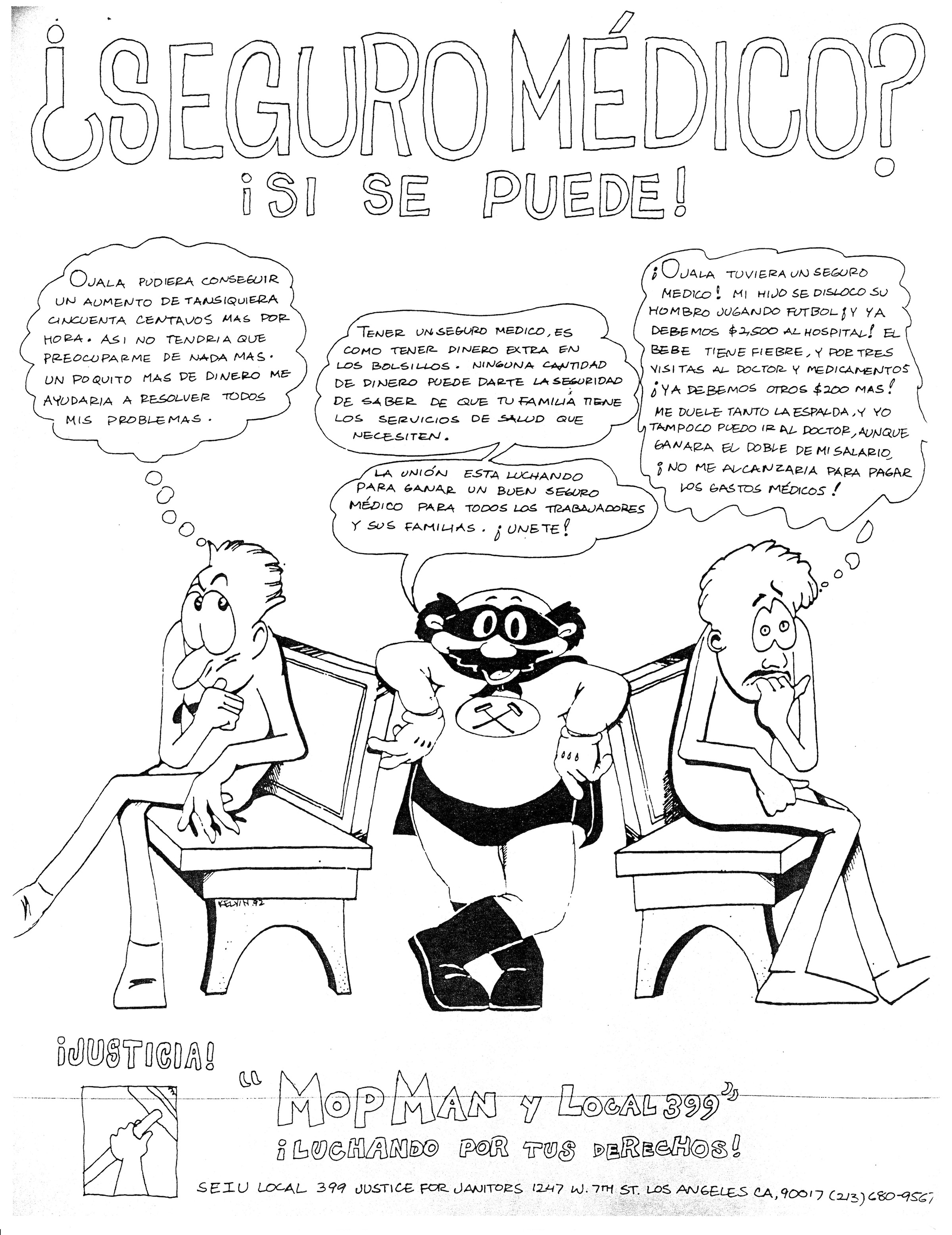

Seguro Medico? Si Se Puede! Mopman y Local 399 Luchando por tus Derechos!

In this cartoon from the Justice for Janitors campaign, two workers worry about the cost of healthcare. The superhero Mopman tells them that having good health insurance is like “having extra money in your pockets.” In cartoons and street theater, the character Mopman was part of the union’s strategy to reach rank-and-file janitors.