After a majority of workers at the New Otani Hotel in downtown Los Angeles supported unionization, hotel management refused to negotiate. Members of HERE Local 11 from other Los Angeles hotels pledged to support the New Otani workers with weekly demonstrations that escalated into long-lasting boycott. This 1996 video produced by HERE Local 11 documents the union’s strategy of targeting the Kajima Corporation, a large Japanese construction firm that was the major stakeholders in the New Otani, which led to alliances with Japanese trade unionists and the Japanese-American community in Los Angeles. An example of “corporate campaigns” that many unions mounted in the 1980s, the boycott campaign focused on Kajima’s role in mid-century Japanese military expansion, the privatization of public services in Japan during the 1980s, and the public development subsidies Los Angeles had provided to Kajima and its partners. The film ends with scenes of a large act of nonviolent civil disobedience in the streets outside the hotel.

“Immigrant workers have always agreed with us philosophically”

In this excerpt of a 1995 speech on multi-union organizing strategy, David Sickler recounts the changing relationship between immigrant workers and organized labor in southern California and identifies some of the mistakes unions have made in their approach to immigrant workers. As the Regional Director for the AFL-CIO and head of the Los Angeles-Orange County Organizing Committee (LAOCOC), Sickler launched the California Immigrant Workers Association (CIWA) to organize undocumented workers into unions. This speech was delivered at the UCLA Labor Center.

Now I’m somebody who’s tried to organize immigrant workers in this town for 20 years. We’ve had some success here and there, but the movement’s never been able to prove to immigrant workers that it could deliver. That it could put its money where its mouth was.

Immigrant workers have always agreed with us philosophically. They know we’re advocates; they know we’re on their side. But they’ve been reluctant to get on board with us on a large scale because they’ve watched our failures. They know that some of our own unions in the past, when they’d go out and organize companies that had immigrant workers, if those workers went on strike and the employer replaced them with other immigrant workers, the union would call the INS and have the scab workers deported. The employer would then call the INS and have the strikers deported. That’s a great deal for immigrant workers. Welcome! Welcome to the institutions of the United States. But the labor movement changed its act in the 70s and the 80s, and we aren’t doing those kinds of things any more. Still, these workers just weren’t sure we could deliver. What happened with the signing of the Justice for Janitors contract sent shockwaves through the immigrant community in Southern California. It will never be the same, ever. Because about six months after the signing of that contract, 900 workers at American Racing Equipment in Rancho Domingas-and I’m telling you it’s 100 percent immigrant-staged a five-day walkout.

Now, I’m an organizer. I’m gonna tell you, 900 workers do not spontaneously walk out of a plant. There’s some leadership in there somewhere. There’s some organizing going on. You hear about hot-shop organizing? This was a super, super red-hot shop. These people organized themselves. And, of course, this is a classic example of how we as a movement respond. The day after 900 workers at American Racing Equipment go out on the street in a wildcat by themselves, 97 unions are out there with their jackets and their leaflets. “Join us; I’m with the Office Workers!” “Join us; I’m with CWA!” “Join us; I’m with the Steel workers!” “Join us; I’m with the IUE!” “Join us; we’re with UAW!”

“People wanted to change things so bad they organized themselves and went into the street.”

On Any Day (1995)

The Tourism Industry Development Board (later known as the Los Angeles Alliance for a New Economy, or LAANE) takes visiting journalists on a tour of four Los Angeles working class neighborhoods. LAANE’s partnership with HERE Local 11 aimed to change the public perception of Los Angeles and highlight the lives of tourism industry workers.

Justice for Janitors 1995 Strike News

English and Spanish TV news coverage of street actions leading up to the 1995 strike by SEIU Local 1877, the Justice for Janitors campaign. Featured speakers include Mike Garcia, Rocio Saenz, and Jono Shaffer. Differences in style and presentation between English and Spanish-language reports suggest parallel public views of unions, inequality, and immigration.

The original video tape and others are available to researchers at the UCLA Library Department of Special Collections:

Pueblo, Unete! Vigil, March, and Mass for Immigrant Rights (1993)

In the fall of 1993, conservative political operatives began circulating plans for an anti-immigrant California ballot proposition, what would become Proposition 187. Advocates of immigrant- and worker-rights raised alarms immediately, and mounted a vigorous opposition campaign. Voters approved Prop. 187 in 1994, but it was struck down by a federal judge. The fight against the anti-immigrant law helped propel a new progressive political coalition in California. This short film documents a vigil, march, and mass held in October 1993 in the name of Father Luis Olivares, the first to declare sanctuary for Central American refugees. It features the actor Martin Sheen and Maria Elena Durazo, president of HERE Local 11.

“They embraced their cause 24 hours a day”

In the summer of 1992, immigrant construction workers across southern California launched a militant strike that surprised both their employers and the Anglo leaders of trade unions. Aided by the California Immigrant Workers Association (CIWA), the drywallers' strike succeeded in improving working conditions in residential construction across the region. This account is from CIWA organizer Jose De Paz. CIWA operated from 1989-1994 as an associate membership organization of the AFL-CIO.

Three main ingredients account for the success of the drywallers strike. First, the determination of the strikers. They were not doing “strike duty”. They embraced their cause 24 hours a day and everything else became secondary to the strike. Additionally, the strikers were aware that they were being oppressed not only as workers but also as Mexicans, which made their bond twice as strong. This came particularly handy when entire families were evicted from their homes for non-payment of rent and had to move in with one or more families in a single dwelling.

Second, organized labor’s considerable contribution to the independent drywall strike fund. In addition to individuals and community organizations, more than 21 AFL-CIO affiliated unions and six Central Labor Councils in California made significant donations to the fund.

Third, CIWA’s unique participation. Besides coordinating legal and immigration defense, CIWA served as a communication bridge between the strikers and police agencies. CIWA also functioned as the strikers’ spokesperson with the media (particularly the Spanish-language media) and as the coordinator of support from Latino community and labor organizations. CIWA’s unique com bination of skills and its dual credentials in the labor and Latino communities enabled it to convert the drywallers’ struggle from a localized labor dispute into a Latino workers movement.

Continue reading ““They embraced their cause 24 hours a day””City on the Edge

Release shortly after the 1992 civil unrest in Los Angeles, City on the Edge criticized the low-wage policies of the tourism industry and challenged political leaders to embrace equitable development. Featuring interviews with historian Mike Davis, business leaders, city officials, and workers, the film offers a glimpse of LA contending with deep social and economic divides.

This video and others are available to researchers at the UCLA Library Department of Special Collections:

Building sustainable peace in Guatemala, the union perspective

From the 1970s to the 1990s, the Central American nations of El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Guatemala experienced civil war, government-sponsored death squads, and genocide. Many who fled the violence settled in Los Angeles were they joined other immigrant workers in low-wage service sector jobs, and became part of the unionization drives of the 1990s. Immigrants workers then mobilized their unions in support of the peace process by welcoming visiting delegations and lobbying federal officials. This flyer documents the visit of Guatemalan union leader Rodolfo Robles to SEIU Local 399 in the early 1990s. His union, representing Coca Cola workers, played a leading role in the opposition to military dictatorship by urban workers. Learn more about Justice for Janitors.

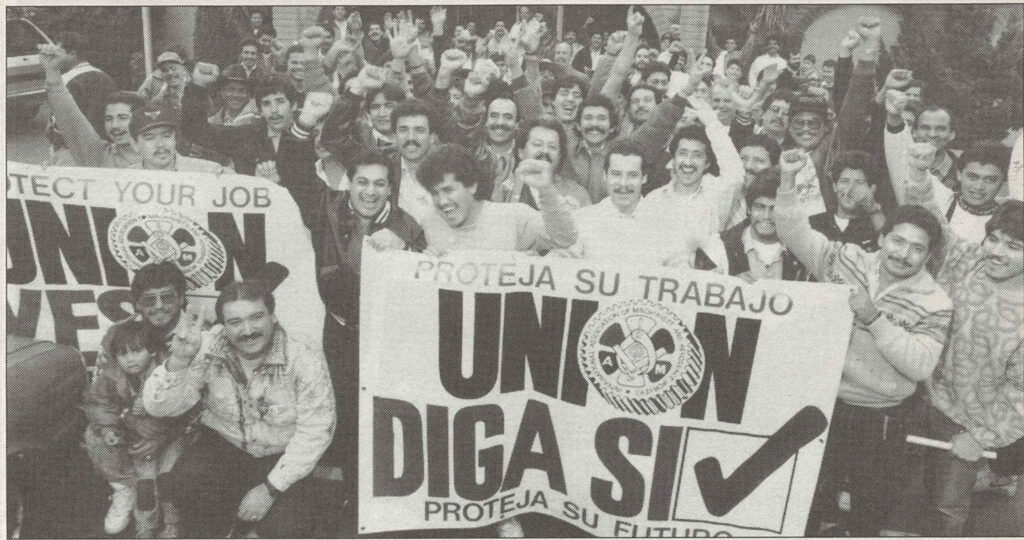

Cleaning Workers to Go on Strike: October 19, 1990

A clipping of a 1990 article describing a Justice for Janitors training held in from of the Los Angeles Police Department. Janitors were preparing to use non-violent civil disobedience in their strike on Bradford Building Services in November of that year. Translated from Spanish by Juan Torres.

“Cleaning workers to go on strike” La Opinion, October 19, 1990

By Miguel Molina

Image caption: Janitors stage an arrest drill to prepare for what will occur as a result of their civil disobedience campaign. To the right, Hispanic women janitors from the same group show signs with slogans. (Picture by Leticia García-Irigoyen/ La Opinion)

Yesterday the committee that organizes cleaning workers announced that on November a strike against the Bradford Company in the buildings in which they provide their service located in the center of Los Angeles and in Glendale.

The union offered courses of civil disobedience to its members in preparation for the strike.

More than 50 cleaning workers participated in this course in front Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) building, located in Parker Center. LAPD Chief, Daryl Gates, was invited to the training but he did not attend.

“This it to show the police that we are not alone and that we are preparing,” warned Jose Orozco, janitor in the campaign against Bradford.

Jono Shaffer, spokesman for the union, assured that the janitors “in Century City learned that it is necessary to prepare ourselves and adopt an attitude of non-violence.”

Peaceful resistance has a long history in this country, said Shaffer. “We have to keep calm in a demonstration or strike and always remember that they are the ones who have to provoke.”

The union assures that during the strike in Century City “we suffered daily provocations by the police that culminated in the police assault on June 15, when dozens of janitors and supporters were chased and beaten.”

The union believes that now LAPD “will not consent to the pressures of the powerful proprietors and their interest.”

Another spokesman for the union, Bill Regen, assures that both parties are trying to overcome the Century City incident.

“The training course helped established a better relationship with LAPD,” said Regen, although he did not explained how. “We established a relationship of trust. Both parties are working to assure that (incidents like the one that occurred in Century City) will not occur again. We are fighting against the corporations, not against the police.”

During the civil disobedience training–which realistically was more of a strike and shut down of the building’s doors training– half a dozen plain clothes police looked on with a smile at the janitors.

Marina Jaco, a Century City strike veteran, said to her janitor partners that civil disobedience is important.

“The owners of the building did not take us seriously when we started to organize,” Jaco said. “They also did not respond when we announced we were going on strike, but they realize that we were willing to win when they saw us sitting outside the doors of their building. Our aggressiveness allows us to succeed on the Century City strike, and I think this will carry to victory in the campaign against Bradford.”

The union accuses Bradford Company for intimidating any efforts to organize workers into a union.

The National Labor Relations Board has received seven complains against Bradford’s illegal intimidation practices, threats, and lay off of workers who have attempted to organize a union.

Most of the workers from Bradford Company are immigrants from Mexico and Central American, who have been compelled to work without pay for weeks, supposedly to train them.

Bradford did not comment on the workers the accusations.

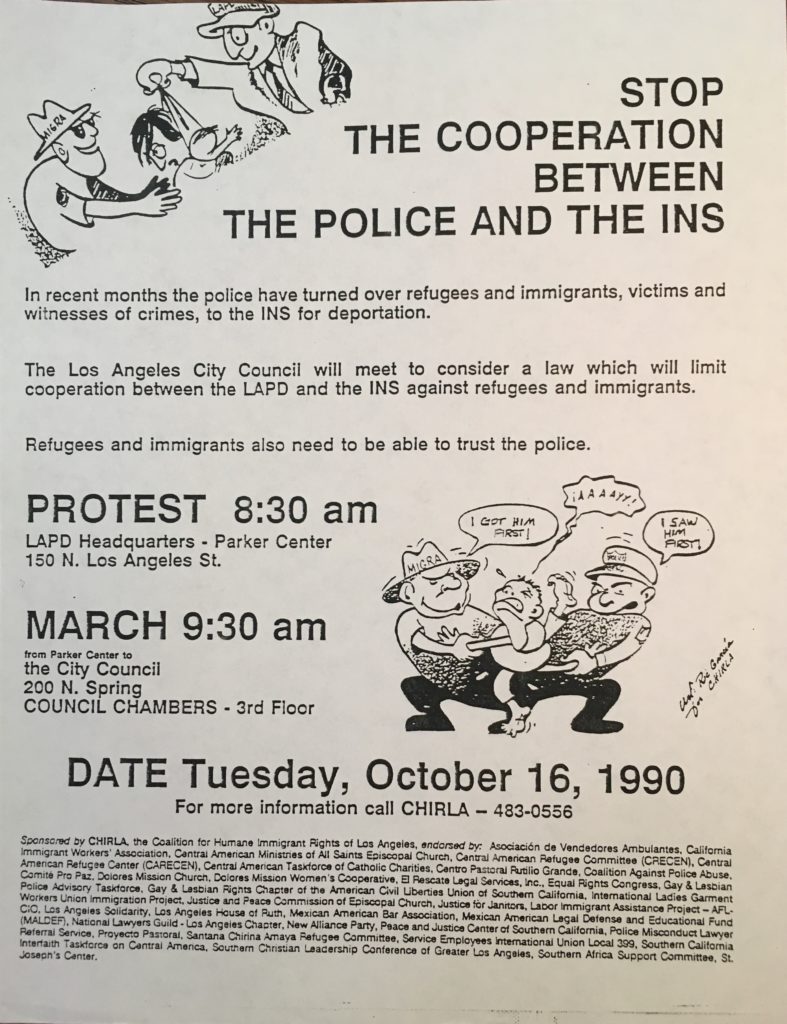

Stop the Cooperation between the Police and the INS

A flyer announcing a protest rally and march organized by the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights of Los Angeles (CHIRLA) in the fall of 1990. Formed in the wake of the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act, CHIRLA drew together organizations and activists from many communities to demand inclusion for immigrants. Reflecting growing progressive coalition in Los Angeles, co-sponsors of this rally included labor unions, religious, civil liberties, and immigrant rights organizations Los Angeles. From the Tom Bradley Papers, Box 1170, folder 9, UCLA Special Collections. Download the Document.