As leader of the Los Angeles County Federation of Labor, Miguel Contreras (1952-2005) reshaped LA’s unions into a powerful political, economic, and social force. The child of farm workers, Contreras was an organizer for the United Farm Workers union (UFW), and later the Hotel and Restaurant Employees union (HERE). He led the Los Angeles County Federation of Labor from 1996 until is death in 2005. The LA Alliance for a New Economy produced this video documenting Contreras’s life story and his impact on the city’s labor movement and working people.

Don’t be a Scrooge: Ghost of Christmas Past visits L.A. City Council

This video produced by the LA Alliance for a New Economy documents elements of the Living Wage campaign in Los Angeles. An actor dressed as the ghost of Jacob Marley from Charles Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol” haunts Los Angeles city hall warning the mayor and council members to consider the needs of low wage workers in December 1996. The council passed the ordinance covering workers for city contractors, and later voted to override the veto of Mayor Richard Riordan in April 1997.

Taking on the New Otani (1996)

After a majority of workers at the New Otani Hotel in downtown Los Angeles supported unionization, hotel management refused to negotiate. Members of HERE Local 11 from other Los Angeles hotels pledged to support the New Otani workers with weekly demonstrations that escalated into long-lasting boycott. This 1996 video produced by HERE Local 11 documents the union’s strategy of targeting the Kajima Corporation, a large Japanese construction firm that was the major stakeholders in the New Otani, which led to alliances with Japanese trade unionists and the Japanese-American community in Los Angeles. An example of “corporate campaigns” that many unions mounted in the 1980s, the boycott campaign focused on Kajima’s role in mid-century Japanese military expansion, the privatization of public services in Japan during the 1980s, and the public development subsidies Los Angeles had provided to Kajima and its partners. The film ends with scenes of a large act of nonviolent civil disobedience in the streets outside the hotel.

“Immigrant workers have always agreed with us philosophically”

In this excerpt of a 1995 speech on multi-union organizing strategy, David Sickler recounts the changing relationship between immigrant workers and organized labor in southern California and identifies some of the mistakes unions have made in their approach to immigrant workers. As the Regional Director for the AFL-CIO and head of the Los Angeles-Orange County Organizing Committee (LAOCOC), Sickler launched the California Immigrant Workers Association (CIWA) to organize undocumented workers into unions. This speech was delivered at the UCLA Labor Center.

Now I’m somebody who’s tried to organize immigrant workers in this town for 20 years. We’ve had some success here and there, but the movement’s never been able to prove to immigrant workers that it could deliver. That it could put its money where its mouth was.

Immigrant workers have always agreed with us philosophically. They know we’re advocates; they know we’re on their side. But they’ve been reluctant to get on board with us on a large scale because they’ve watched our failures. They know that some of our own unions in the past, when they’d go out and organize companies that had immigrant workers, if those workers went on strike and the employer replaced them with other immigrant workers, the union would call the INS and have the scab workers deported. The employer would then call the INS and have the strikers deported. That’s a great deal for immigrant workers. Welcome! Welcome to the institutions of the United States. But the labor movement changed its act in the 70s and the 80s, and we aren’t doing those kinds of things any more. Still, these workers just weren’t sure we could deliver. What happened with the signing of the Justice for Janitors contract sent shockwaves through the immigrant community in Southern California. It will never be the same, ever. Because about six months after the signing of that contract, 900 workers at American Racing Equipment in Rancho Domingas-and I’m telling you it’s 100 percent immigrant-staged a five-day walkout.

Now, I’m an organizer. I’m gonna tell you, 900 workers do not spontaneously walk out of a plant. There’s some leadership in there somewhere. There’s some organizing going on. You hear about hot-shop organizing? This was a super, super red-hot shop. These people organized themselves. And, of course, this is a classic example of how we as a movement respond. The day after 900 workers at American Racing Equipment go out on the street in a wildcat by themselves, 97 unions are out there with their jackets and their leaflets. “Join us; I’m with the Office Workers!” “Join us; I’m with CWA!” “Join us; I’m with the Steel workers!” “Join us; I’m with the IUE!” “Join us; we’re with UAW!”

“People wanted to change things so bad they organized themselves and went into the street.”

On Any Day (1995)

The Tourism Industry Development Board (later known as the Los Angeles Alliance for a New Economy, or LAANE) takes visiting journalists on a tour of four Los Angeles working class neighborhoods. LAANE’s partnership with HERE Local 11 aimed to change the public perception of Los Angeles and highlight the lives of tourism industry workers.

Justice for Janitors 1995 Strike News

English and Spanish TV news coverage of street actions leading up to the 1995 strike by SEIU Local 1877, the Justice for Janitors campaign. Featured speakers include Mike Garcia, Rocio Saenz, and Jono Shaffer. Differences in style and presentation between English and Spanish-language reports suggest parallel public views of unions, inequality, and immigration.

The original video tape and others are available to researchers at the UCLA Library Department of Special Collections:

On a mission to organize immigrant workers

Launched in 1989, the California Immigrant Workers Association (CIWA) supported a number of break-through union campaigns with immigrant workers. David Sickler, regional director for the AFL-CIO, conceived of CIWA as a way to funnel support for the many organizing drives that developed in the wake of the Immigration Reform and Control Act. CIWA staff provided legal and organizing aid to immigrant workers and connected them with unions, and advised unions on organizing best practices. However, in the spring of 1994 national leaders of the AFL-CIO decided to stop funding the program. In this memo, Sickler and CIWA staffer Jose De Paz appeal to southern California union leaders to help fund CIWA. The demise of CIWA came just months before immigrant rights groups and unions scrambled to fight the anti-immigrant Proposition 187 in the November 1994 election. View the document.

From the UNITE HERE Local 11 Records, Box 17 Folder 6, UCLA Library Department of Special Collections.

Pueblo, Unete! Vigil, March, and Mass for Immigrant Rights (1993)

In the fall of 1993, conservative political operatives began circulating plans for an anti-immigrant California ballot proposition, what would become Proposition 187. Advocates of immigrant- and worker-rights raised alarms immediately, and mounted a vigorous opposition campaign. Voters approved Prop. 187 in 1994, but it was struck down by a federal judge. The fight against the anti-immigrant law helped propel a new progressive political coalition in California. This short film documents a vigil, march, and mass held in October 1993 in the name of Father Luis Olivares, the first to declare sanctuary for Central American refugees. It features the actor Martin Sheen and Maria Elena Durazo, president of HERE Local 11.

“They embraced their cause 24 hours a day”

In the summer of 1992, immigrant construction workers across southern California launched a militant strike that surprised both their employers and the Anglo leaders of trade unions. Aided by the California Immigrant Workers Association (CIWA), the drywallers' strike succeeded in improving working conditions in residential construction across the region. This account is from CIWA organizer Jose De Paz. CIWA operated from 1989-1994 as an associate membership organization of the AFL-CIO.

Three main ingredients account for the success of the drywallers strike. First, the determination of the strikers. They were not doing “strike duty”. They embraced their cause 24 hours a day and everything else became secondary to the strike. Additionally, the strikers were aware that they were being oppressed not only as workers but also as Mexicans, which made their bond twice as strong. This came particularly handy when entire families were evicted from their homes for non-payment of rent and had to move in with one or more families in a single dwelling.

Second, organized labor’s considerable contribution to the independent drywall strike fund. In addition to individuals and community organizations, more than 21 AFL-CIO affiliated unions and six Central Labor Councils in California made significant donations to the fund.

Third, CIWA’s unique participation. Besides coordinating legal and immigration defense, CIWA served as a communication bridge between the strikers and police agencies. CIWA also functioned as the strikers’ spokesperson with the media (particularly the Spanish-language media) and as the coordinator of support from Latino community and labor organizations. CIWA’s unique com bination of skills and its dual credentials in the labor and Latino communities enabled it to convert the drywallers’ struggle from a localized labor dispute into a Latino workers movement.

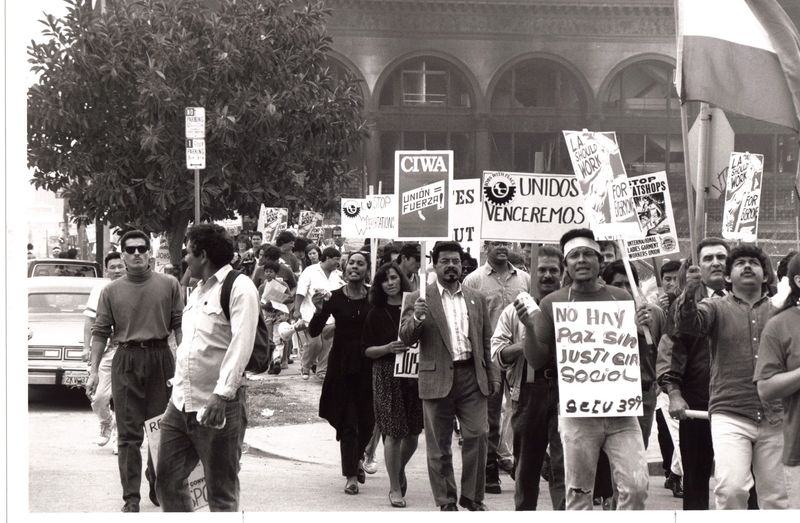

Continue reading ““They embraced their cause 24 hours a day””No peace without social justice, 1992

Marchers carry signs and banners from a variety of Los Angeles community organizations and unions, including one from Local 399 reading “No Hay Paz sin Justicia Social” (No Peace without Social Justice). A handwritten note on the back of the photograph appears to read “J for J Rent Protest 5/92” suggesting a connection to the civil unrest of April 29-May 4, 1992.